The Newest Member of the Human Family Prompts More Questions Than it Answers

The discovery of a new human ancestor, Homo Naledi, has made more headlines than any other paleontology discovery so far this year. The natural interest most people have in our ancestors has been propagated by the spotty nature of the fossil record anthropologists (scientists who cross paleontology and archeology to study early humans) focus on. Although early human ancestors (Hominins) are not necessarily more poorly represented than other families of organisms, anthropologists cannot be contented with this, and hominins sit the border in geologic age where their remains do not conform to standards regularly. Some are old enough to be true fossils, in which all the bone has been replaced by minerals, others are just bone. Some can be easily dated and identified, but not all can. As such many new discoveries can lead to some sensational and dramatic articles, as anthropologists debate and attempt to piece together how the new specimen fits into the family tree as it understood. However, that understanding is often a spotty and controversial.

Hominins are generally divided into two broad categories. The first is an ever shifting assortment of primitive* australopithecus-like genuses, filled with creatures resembling walking chimpanzees and stunted, hairy humans. The second is the genus Homo, which contains more than 15 species, a surprisingly large number for a large mammal genus. Many anthropologists argue that Homo is due for revision, as it contains both modern humans and our closest relations and species such as Homo Erectus that were still hairy and had brains a third of our size. On matters of classification anthropologists are sharply divided, some argue that there are too many species both of primitive hominins and Homo while others argue the exact opposite. Oftentimes this is the result of the relatively small differences between different specimens, as they all share exactly the same body plan, though with variations that are sometimes quite major.

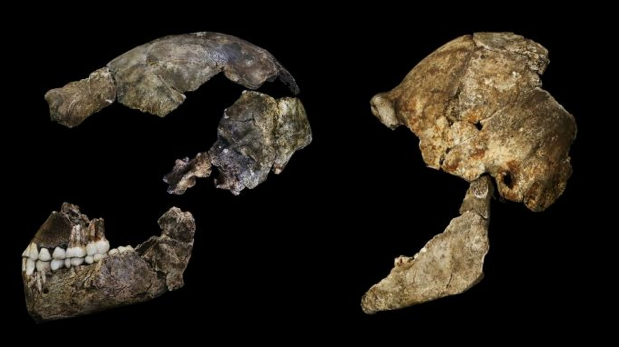

Homo Naledi was discovered in a cave in South Africa by two daring spelunkers who wriggled through a very narrow vertical crevice only to find themselves in a wider chamber whose floor was littered with the bones of many specimens of Homo Naledi. The anthropologist they told about their find, Lee Berger, could not fit down into this crevice, being neither skinny nor a trained spelunker, so he orchestrated an excavation with a team specifically chosen for their crevice worthy physiques. They worked efficiently, and cleared out a grand total of 1,550 individual bones from at least 15 individuals in various stages of fossilization. From there Berger organized an unorthodox “open house” in which 60 anthropologists, including several grad students and other aspiring anthropologists. Working alone, it would have taken Berger many years to complete this project, but with this aid the formal statement was able to be published in the relatively brief time of two years, from 2013 to 2015. However, there were a few hitches that made details of the discovery uncertain, which would prompt debate in the anthropology community.

The first of these issues was Homo Naledi’s bizarre combination of primitive and derived features. Some examples of these include teeth that appear modern on roots that appear primitive, hands with the modern bone assortment but curved fingers like those of a climbing primate, and hips that are similarly part primitive and part derived. Another telling feature is the braincase size: half that of our own. This meant that it was smarter that the average Homo Erectus, but nowhere close to human. This mismatch of features led many anthropologists to wonder about Berger’s initial classification of Homo Naledi as a primitive or even basal Homo species. Some argued that it was a variety of Homo Erectus, and that Berger and company had underestimated the diversity within this species. In this matter Berger has maintained his position despite criticism.

The second issue pertains to how the bones reached their final resting place. There is no evidence of any habitation, such as tools or discarded bones from food, and no easy way in or out. Therefore these Homo Naledi do not seem to have been living in the cave. Additionally, there is no evidence that the cave was once a sinkhole, a sort of natural trap that would have sent these creatures tumbling to their deaths. The ceiling is just not right for that. Berger’s shocking solution to this puzzle is that the specimens were interred in ritual burial. Many anthropologists, even those who agree that there is no other possible explanation, consider this an affront to established conventions of anthropology. Until now, it had been tacitly accepted that ritual was beyond the grasp of all but the most intelligent species of Homo, so this raises unanswerable questions about just how much mental capability is required for mental activities centered around reflection.

The third and most technical of these issues has to do with the age of Homo Naledi. While description of the fossils was underway, Berger declined to destroy some of the bones for carbon dating. This process scans for the radioactive form of carbon and does half life calculations to show the rate at which it has deteriorated over time. It can exactly date organic remains from up to 50,000 years ago. Berger hopes to get a reading on the carbon dating now that publishing is done, as the other methods of dating will prove arduous or are simply impossible. For example, studying the decay of trace amounts of radioactive uranium in flowstones (which works for fossils many millions of years old), rocks laid down from sand in water, will be difficult because the relative age of flowstones in a cave is almost impossible to determine. Using the standard form of dating used for rocks that are millions of years old, biostratigraphy, is likewise impossible because the bones were not buried within a rock formation but exposed in a cave older than them. So this means that if the age of Homo Naledi is over 50,000 years old (which would be remarkably young) there will be no easy way to determine age. This is upsetting to all anthropologists as it means the evolutionary significance of Homo Naledi may go unknown for a very long time.

For more information consider the following sources:

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/09/150910-human-evolution-change/

*Evolutionary Theory Time: It must be noted that the use of the word primitive in paleontology is not the same as the typical connotations would suggest. “A primitive organism” simply means one which has many traits similar to those of its ancestors. The opposite of this term is not advanced, but instead “derived”, in reference to the derived organism’s modification of ancestral traits. Primitive does not necessarily indicate a level of fitness lower than that of more derived relatives, because each organism is specifically adapted to its own environment, and for some organisms the adaptations of their ancestors are those needed in their environment. The scientific name for a primitive trait is a “plesiomorphic trait”. Examining various species for similar plesiomorphic traits known as “symplesiomorphic traits” is a general method used for demonstrating common ancestry between them. An organism or grouping of organisms which is the most primitive of all the organisms within its classification is referred to as basal.

Whitney • Oct 1, 2015 at 2:08 pm

Evolutionary Theory Time is my favorite time