A Novice’s Take on “To Pimp a Butterfly”

An experience.

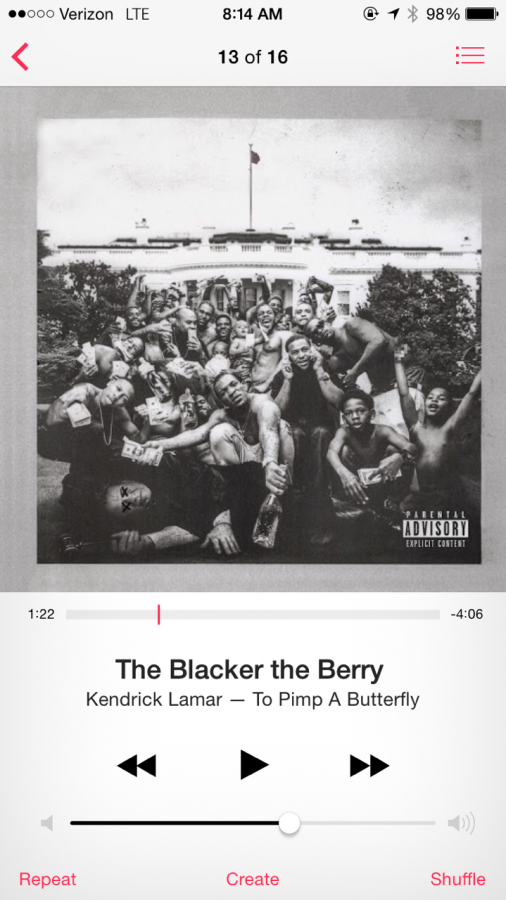

I don’t listen to hip hop. Like, ever. My friends and I had this one summer where we listened to a lot of Mac Miller but I really don’t think that counts. In listening to Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, however, I saw the newly redefined art form for what it is: a powerful medium of self-expression, social commentary, and even protest. The album, released on March 17th to incredible hype following Kendrick’s critically acclaimed good kid, m.A.A.d city, broke the record for most streamed on released day, and for good reason; TPAB is ground-breaking, emotional, and redefines Kendrick as hip hop’s new messenger.

TPAB is underscored by an extended metaphor and a poem, written in pieces as the album progresses. The metaphor, and the albums title, allude to the corrupting nature of both hood culture and fame, a process by which young artists attempt to break the cycle of poverty, institutionalized racism, and pressure into violence. Throughout its 79-minute runtime, TPAB serves as explosive commentary on issues faced by poor black people, including police brutality, discrimination, and crippling gang violence. Oscillating between intensely personal and outward-looking and socially conscious, TPAB moves through Kendrick’s mind, revealing his genius, his pain of leaving home, and his unbearable survivor’s guilt. To Kendrick, fame and heritage endure bitter conflict, exposing the chains of both societal racism and his urban roots.

The theme of heritage shows up often in TPAB, more often in the redemptive second half. The album is unabashedly black, written quite obviously for black audiences about black issues about which sympathy from most white audiences is not enough and empathy from them is impossible. Kendrick’s focus on black issues, however, is not completely lost on white audiences, says senior Geoff Schiller. “I love how racially charged this album is. Kendrick is such a famous rapper that people from all walks of life listen to… I can’t see how this record wouldn’t make people think more.” The “black is beautiful” theme is blunt and celebratory; “Complexion (A Zulu Love)” rejects typical white conventions of beauty while “The Blacker the Berry” focuses on racial self-hatred and the reclamation of black stereotypes. Statements of black power show up in “King Kunta” and “i”, with Kendrick comparing the slave protagonist of Roots, Kunta Kinte, to a monarch, highlighting the stereotypically and reprehensibly oxymoronic nature of the “successful black man” narrative that Kendrick rightfully rejects. The album’s proud blackness is even present in the music and production; the beats are heavily influenced by funk and jazz, a genre once referred to by singer Nina Simone as “black classical music”.

Kendrick’s success is another sore point he expresses on TPAB, demonstrating fear of being perceived as disingenuous and disconnected. On “You Ain’t Gotta Lie (Momma Said)”, he wistfully asks people to be real with him, but recognizes the painful importance of image and reputation. His success alienates him from home, an isolation he attempts to grapple with in “u”, “Momma”, and “Hood Politics”. His disconnection from his hometown of Compton through his fame makes him a voice for his people, but a voice that is not quite representative of them. Returning home is painful and his guilt of escaping the violence and suffering of his former neighbors cripples him and cuts him off from the roots that made him famous. He often accuses the music industry and American people of soliciting his genius for their benefit, both in his extended metaphor and the jazzy “For Free? (Interlude)”.

His melancholy shifts halfway through the album in “Alright”, evolving into a reclamation of black pride and abandoning the mask of braggadocio in favor of genuine self-esteem. Kendrick shines across all of his emotions, reflected even in his voice, which goes from cracked to booming as he treks through his history. The penultimate song, the Grammy-winning “i”, is Kendrick’s last hurrah, embracing his heritage (“I love myself”) and his artistry. “i” is followed by perhaps the album’s most powerful song “Mortal Man”, which shows off Kendrick’s genius and solidifies TPAB as a quick masterpiece. His questioning of loyalty and the theme of posthumous resentment in the vein of the “If They Gunned Me Down” hashtag demonstrates the instability of his art and his position. With “Mortal Man”, however, he takes up the torch as this generation’s messenger, following in the footsteps Malcolm X and Tupac Shakur, the latter of whom makes a powerful appearance in the album’s final minutes, displaying the cross-generational nature of issues faced by black Americans. With TPAB, Kendrick recognizes the ephemeral power he gained through success as well as responsibility that goes with it.

TPAB is perhaps one of the most powerful works of art I’ve ever experienced, an opinion shared by senior Will Wraith. “He brings art and self-expression to the limelight, especially since he’s such a huge figure in the hip hop game right now,” he says. This is not an album to jam out to in the car or to play at a party, this is a personal and emotional recount of Kendrick’s history as a black artist that requires time and patience to appreciate. Do not listen to it once to dance to the beat of “King Kunta”, infectious as it may be. Put in your headphones, open up the lyrics, listen wholeheartedly. As senior Doug Witte, friend and personal hip hop guru puts it, “Don’t sleep on Kendrick. Too many people are ignoring this album. People want an album to ‘bump in the car’. Give it a chance, listen to what he’s saying.” And as Kendrick puts it himself, he is not here for your entertainment. He is a storyteller. Take the time to listen, and listen well.

Nick Simeone • Feb 14, 2018 at 11:05 pm

Wow. Pure excellence in writing form. Thank you for allowing my eyes to read this.